Shearing is a metal fabricating process used to cut straight lines on sheet metal. Material is cut (sheared) between the edges of two opposed cutting tools. It works by first clamping the material with blank holders. During the shearing process, a moving blade comes down across a fixed blade with the gap between them determined by a required offset.

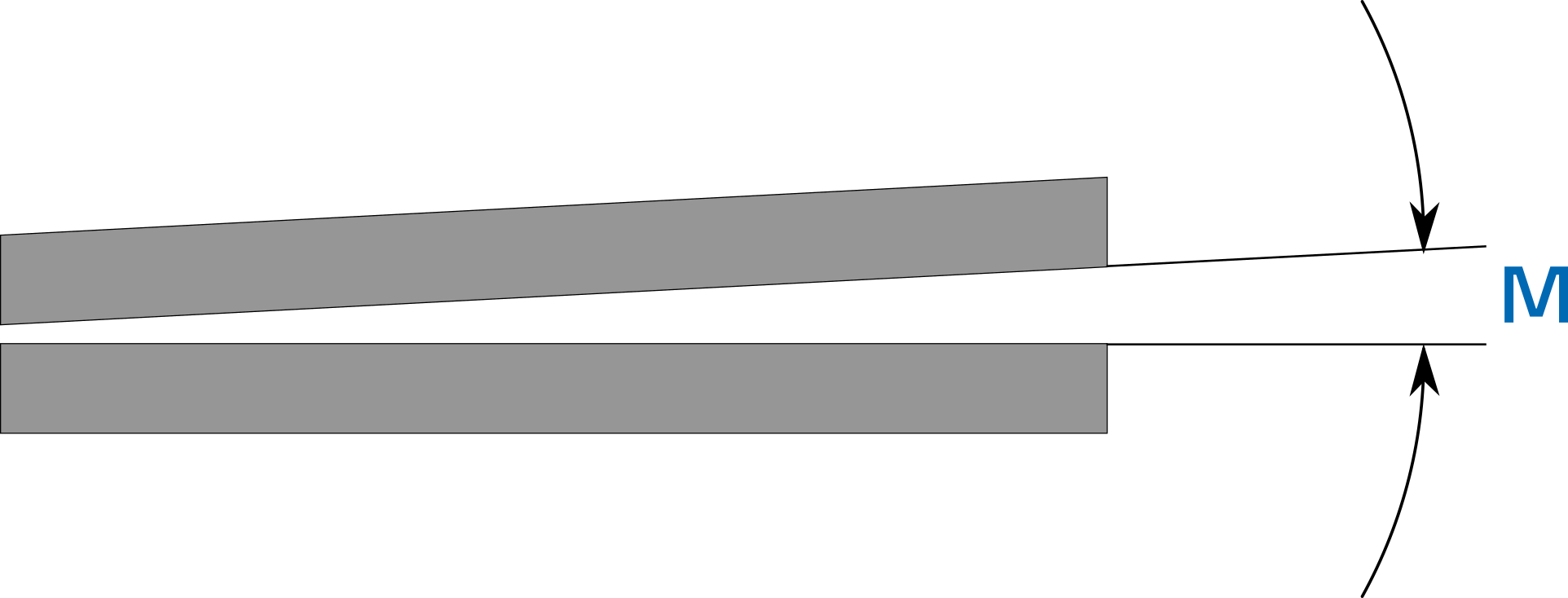

The moving blade may be set at an angle in order to shear the material progressively from one side to the other; this angle is referred to as the shearing angle or raking angle (M). A higher angle decreases the amount of force required, but increases the stroke.

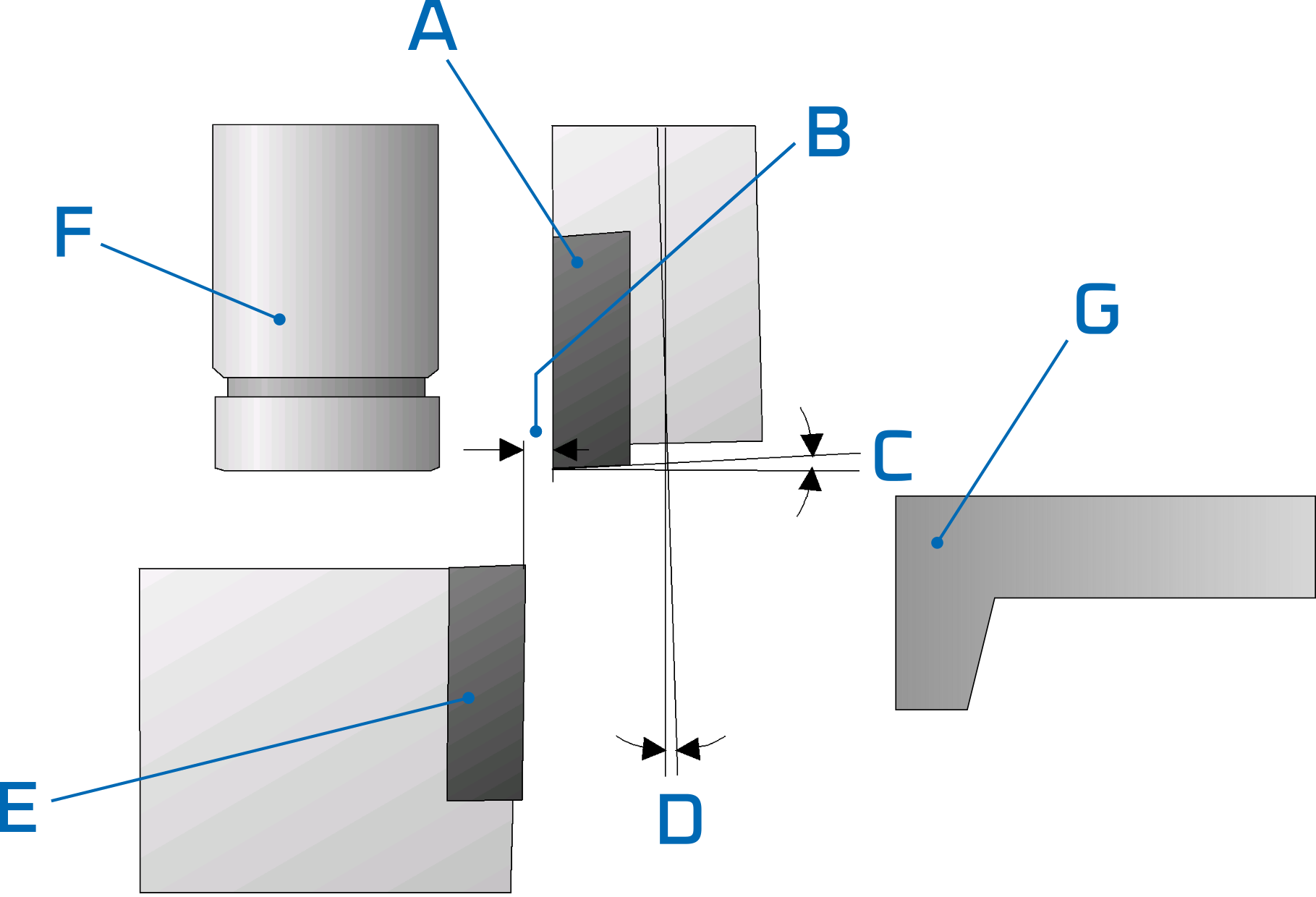

As far as equipment is concerned, the machine consists of a shear table, blank holders (F), upper and lower blades (A, E), and a backgauge (G), used to ensure that the workpiece is being cut where it is supposed to be. A back support is often found to support the sheared part, with optional automatic unloading or stacking.

To get a perfect cut you need a high-quality shear, able to reduce the effects of variable sheet metal characteristics, internal stresses, and geometry. These natural effects, if not corrected and compensated, become defects in final product, reducing their quality.

Cutting angle

It is the angle (C) of the cutting edge of the blade. It slightly influences shearing force: using two square edge blades requires higher cutting force than if the upper blade is ground at a slight angle, usually to a maximum of 87°. Lower blade is always at 90°.

90° blades are called “four-edge” blades and can be turned to use all of its 4 edges. Angled blades are called “two-edge” blades and can be turned to use only 2 edges. Opposite edges have an angle greater than 90° and therefore cannot be used for shearing.

Shearing angle

Shearing angle (M) has a great effect on shearing force and has an important effect on twisting, which can occur when shearing thin strips. Shearing angle is less than 3°.

Blade clearance

Blade clearance is the perpendicular distance (B) between the shearing blades. Exact cutting clearance depends on plate thickness and material strength. Accurate values must be determined for each case. If the cutting clearance is too small tool wear increases: tooling costs and cutting force will be higher. If cutting clearance is too large, the material is drawn between the two blades. The result will be a cut edge with increased taper and larger plastic deformation. Cutting clearance is a key factor for edge quality.

As a rule of thumb for mild steel, blade clearance is set to 0,06 mm per each mm of plate thickness up to 10 mm, and to 0,04 mm per each mm of plate thickness over 10 mm. In imperial units, blade clearance is set to 0.06″ per each inch of plate thickness up to 1″, and to 0.04″ per inch of plate thickness over 1″. For example, a 16-mm thick plate should be cut with a 0,04×16 = 0,64 mm blade clearance. In imperial units, a 1/2″ plate should be cut at 0.06″x0.5 = 0.03″ blade clearance.

Clearing angle

Blade ram is not perfectly vertical, but tilted poiting towards the back to facilitate piece separation. The clearing angle (D) is fixed and usually set to 1,5°.

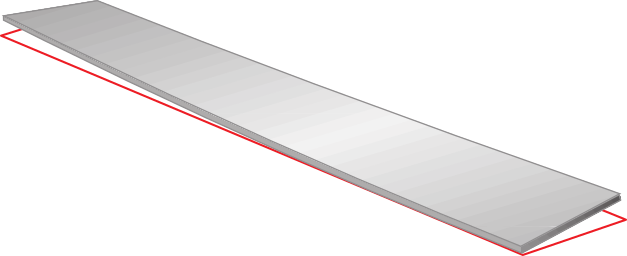

Common shearing defects are: twisting, straightness error (crooking), bowing, and poor edge quality.

Twisting

This defect twists the plate along its axis. It typically happens when shearing narrow strips (less than 10 times the thickness). Shearing conditions that increase this defect are related to sheet metal geometry (high thickness, reduced width, short length), material characteristics (soft material, uneven stress distribution) and of course cutting parameters (high rake angle, high cutting speed).

To reduce this defect we recommend lowering the rake angle. It is also useful to add an anti-twist device. This option consists in a series of hydraulic cylinders that push the plate against the top blade. This opposing force is applied during shearing, proportional to the plate thickness.

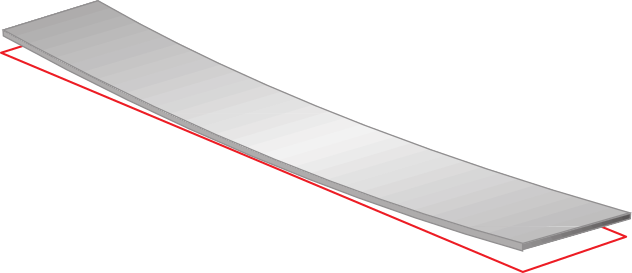

Crooking

This defect produces a plate that is curved along its plane (surface stays flat). It is related to strip width, its thickness, material strength and previous cold rolling direction (residual stresses). To reduce crooking it is recommended to use a smaller shearing angle and to do pre-cuts along rolling direction.

Another major cause is using a guillotine shear where blade ram is only supported at its ends, instead of over its entire length. During shearing the blade will become crooked because of the cutting force and will tend to open in the center. To eliminate the root cause of this problem, we recommend choosing a shear with adjustable blade pads that will oppose this deflection so as to keep the blade perfectly linear.

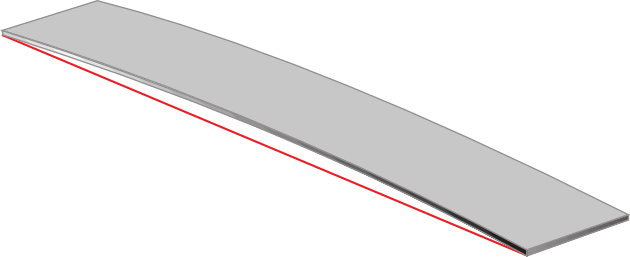

Bowing

This effect results in a bowed sheet metal: the sheet metal is no longer flat as its edges raise from the plan. This defect is related to cutting angle and plate strength. To reduce this effect it is recommended to use a smaller shearing angle (M) and to hold the sheet metal with a back support.

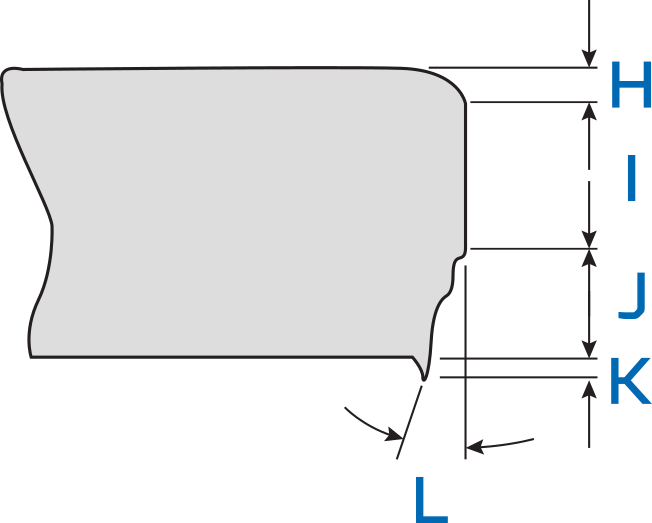

During shearing, material initially deforms plastically in a very small region (H), causing a residual deformation. Afterwards, the upper blade penetrates the material forming a clean zone (I) where cutting is neat and regular. Close to the end of the shearing, material gives in and cracks, producing a rough and irregular surface known as the fractured zone (J), which extends into the edge burr (K). Fractured zone is often not perpendicular to the plate but at a variable angle (L).

To improve edge quality you must adjust blade clearance (B), and keep blade wear under control.